For quite a few months now, I've been one of the guardians of Wikipedia's article on transhumanism, a job that I'm quite proud of - I think we've produced a worthwhile resource. To be honest, I might have done it differently if I'd been working by myself, but then again it would never have happened without the energy of the other two people who were mainly involved (energy that often seems to exceed my own). So, everything I'm about to say is in the context of my considering this to be a fine piece of work, well worthy of its Featured Article status at Wikipedia and useful, at least as springboard, to anyone who would like to study transhumanism seriously.

Much of the article is devoted to reporting criticisms of transhumanism ... and defences against those criticisms. This is one thing that I'd change somewhat, if I could, partly because it puts a disproportionate weight on controversies, but partly for another reason. The article ends up recounting arguments for and against all sorts of things that don't necessarily go to the heart of transhumanism at all. It puts arguments against transhumanism that actual transhumanists have not necessarily recognised as such, or responded to as if this were necessary in order to defend transhumanism itself.

Transhumanists advocate the use of technology to increase human cognitive and physical capacities and the human life span - though they have widely varying views about what moral constraints apply to the means that may be used. And that's about all they need have in common.

By this simple definition, we should all be transhumanists. I don't see why we need to adopt some more restrictive definition, and I don't see why transhumanists as such should be committed to any other particular project, such as creating fully-conscious artificial intelligence, attempting to upload our personalities onto advanced computational devices, uplifting non-human animals, producing fully-formed human-animal hybrids with human-level intelligence ... and so on. (In my own case, I have substantial reservations about all the above, but I have been prepared elsewhere to "stand up and be counted" as identifying with the transhumanist movement, and I see no reason to recant at this stage of events.) These particular projects are advocated by particular transhumanists who are prominent in the relevant debates, but they are not what I see as the essence of transhumanism. Accordingly, the Wikipedia article seems a bit misleading, and this problem pervades much of its text.

Whatever reservations I have about any of these projects - uploading, uplifting, or whatever - their opponents often argue in ways that seem bizarre. One part of the Wikipedia article with which I've had relatively little involvement, partly because I'm rather confused by it, expounds something that it calls "The Frankenstein argument". The argument goes like this (some references, etc., removed for clarity; some minor reformatting for the same reason):

[...] bioconservative activist Jeremy Rifkin and biologist Stuart Newman argue against the genetic engineering of human beings because they fear the blurring of the boundary between human and artifact. Philosopher Keekok Lee sees such developments as part of an accelerating trend in modernization in which technology has been used to transform the "natural" into the "artifactual". In the extreme, this could lead to the manufacturing and enslavement of "monsters" such as human clones, human-animal chimeras, or even replicants, but even lesser dislocations of humans and nonhumans from social and ecological systems are seen as problematic. The novel The Island of Dr. Moreau(1896) and the film Blade Runner (1982) depict elements of such scenarios, but Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein is most often alluded to by critics who suggest that biotechnologies (which currently include cloning, chimerism and genetic engineering) could create objectified and socially-unmoored people and subhumans. Such critics propose that strict measures be implemented to prevent these potentially dehumanizing possibilities from ever happening, usually in the form of an international ban on human genetic engineering.

There seem to be many things going on here - which is fair enough, in a sense, since the article is trying to cover a range of criticisms by different people. As far as I can work out, there is, first of all, supposed to be something intrinsically wrong about "blurring the boundaries" between human and artifact. I cannot imagine what this is. IVF babies, for example, may be thought of as "artifactual" in the sense that they are produced through technological intervention, rather than in the time-honoured manner we inherited from our mammalian ancestors, but no one rational argues that there is anything wrong with conceiving children by IVF (or that their technologically-mediated origin would justify mistreating those kids once they're born).

We are appropriate objects of each other's concern and respect because of our actual intrinsic properties, such as our vulnerability to suffering and our capacity for reason - and perhaps, I'd argue, because of our psychological propensity to bond with each other and form solidaristic communities - not because most of us happen to have been conceived without technological intervention.

Similarly, I am not an "artifact", in any morally relevant sense, because my appendix was removed when I was a child ... but I guess I would not be alive now - I'd have died a few decades ago - but for that technological intervention. Many of us reading this post still exist, right now, partly because of specific acts of technological artifice that prolonged our lives. This element of artifactuality (in a non-moral sense) says nothing about how we deserve to be treated or how we are inclined to treat each other.

There is also a fear of "monsters" reported in the Wikipedia article, or perhaps it is just a fear that we will create persons who will be seen as monstrous and consequently enslaved. In the end of the para, there's also something about "dehumanizing" possibilities, but it is difficult to nail down exactly what dehumanisation, exactly, has to do with any of this. Who is being dehumanised, and in what sense?

We dehumanise people, in a morally reprehensible sense, when we treat them in a way that is not responsive to their basic needs as human persons. We might enslave them, or "merely" pressure them into employment under sweatshop conditions; we might starve, abuse, and torture them; we might treat them as if they are irrational and cannot make their own life choices; we might deny their freedom to express themselves through speech and art; we might try to destroy their sexuality with puritan indoctrination at an early age or by such outrages as female genital mutilation; we might teach them, when they are still too young to challenge it, that curiousity and scepticism are bad - and so on.

It might be that non-human "monsters" with humanlike needs and capacities would, in an anologous sense, be dehumanised if we ended up enslaving them. However, there seems to be a suggestion in the Wikipedia passage (or the arguments it reports) that someone is somehow being dehumanised just because a technology such as somatic cell nuclear transfer might be used for reproduction, irrespective of whether anyone is subsequently enslaved. But that would apply to reproductive cloning no more than it applies to IVF or to the numerous technological interventions we make to prolong (as opposed to initiating) human life. Someone who comes into the world through conception by somatic cell nuclear transfer would not thereby be dehumanised at all.

I hardly know how to begin criticising arguments that invoke Frankensteinian fears, because they seem to combine appeals to irrational yuck-factor responses with more rational concerns that certain categories of future persons might be mistreated. Perhaps some other word or phrase should be used in the previous sentence, rather than "rational" ("clearly articulable"?), because the actual kinds of mistreatment imagined often seem far-fetched.

If the concern is that we will create humanlike slaves, surely the answer is that this imagines a program of creating persons whose rights (to use moral shorthand that I'm not overly fond of) we would then turn around and violate grossly. So of course, that is not a path we should take. I'm not aware of any self-identifying transhumanist who has suggested such a thing, and in any event it's not some idea essential to transhumanism - so how, exactly, is opposition to it a critique of transhumanist thought?

Admittedly, some other people have made proposals from time to time that arguably involve a form of slavery, or something with a resemblance to it. Such possibilities are often presented in science fiction, though usually not with approval. The superchimps described by Arthur C. Clarke in Rendezvous with Rama seem like a relatively benign version of the idea - one on which the author does actually appear to bestow approval. However, if this is the sort of thing that is objected to by the Frankenstein argument, the argument is in trouble. Clarke's superchimps are not human. They are simply very highly intelligent animals that are trained to do some jobs in space. They are actually much better treated than most domestic animals, human slaves, and factory employees have been in the past.

Perhaps there is still something morally wrong in Clarke's scenario - after all, even ordinary chimpanzees seem to have a conception of themselves, and are perhaps inappropriate subjects for training to carry out our tasks - but it is not intuitively shocking. If we want to rule out this kind of program for using ordinary or genetically modified apes as work animals, let's do so by supporting such things as the Great Ape Project.

Actually, I don't believe that we should take the step of creating unique, non-human persons (pig-men, cheetah girls, super-superchimps, or whatever) - at the risk of condemning them to lives of alienation and loneliness. That, however, is a completely different scenario from simply bringing a human child into the world by somatic cell nuclear transfer, or bringing into the world a child who has been given a great gift by having her individual genome manipulated - say, for unusual resistance to ageing or for a propensity, in standard human environments, to develop unusually high intelligence. Nothing rational in the Frankenstein argument addresses this sort of scenario, even though it seems that the argument is meant to have wide application and one of its conclusions is supposed to be that we should ban human genetic engineering.

Bioconservatives continue to generate intellectually confused arguments that go nowhere towards establishing a rational critique of the more moderate proposals favoured by transhumanists (and by a large number of secular bioethicists who don't necessarily identify with transhumanism). The bioconservative arguments are typically so bad that I often feel I have to provide my own critique, just so that transhumanists' proposals get some decent rational testing.

Unfortunately, the debate about emerging technologies that could alter human capacities has long been hijacked by people who appear to be ... let's be blunt ... simply enemies of liberty and reason. A lot of work still needs to be done just to disentangle the more rational fears of what might happen with emerging technologies (hint, I have nothing against Peter Singer's totally sensible expressions of concern) from all the fundamentally irrational ones.

About Me

- Russell Blackford

- Australian philosopher, literary critic, legal scholar, and professional writer. Based in Newcastle, NSW. My latest books are THE TYRANNY OF OPINION: CONFORMITY AND THE FUTURE OF LIBERALISM (2019); AT THE DAWN OF A GREAT TRANSITION: THE QUESTION OF RADICAL ENHANCEMENT (2021); and HOW WE BECAME POST-LIBERAL: THE RISE AND FALL OF TOLERATION (2024).

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Monday, September 25, 2006

I've done it ... maybe

I'm running late here but I think I might actually have that article on science fiction finished. It's "only" 3,500 words but very compressed and quite densely argued - I feel like I've been writing a short book on the subject.

I'll sleep on it tonight, and tomorrow I'll see if I'm prepared to submit the current version.

I'll sleep on it tonight, and tomorrow I'll see if I'm prepared to submit the current version.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Mid-semester break at last

I'm looking forward to a week's break from teaching responsibilities. I hope my students enjoy the break, as well - though they have an essay to worry about.

I'm looking forward to a week's break from teaching responsibilities. I hope my students enjoy the break, as well - though they have an essay to worry about.I've had a hectic week here, partly because I seem to be having computer or internet problems wherever I go at the moment. The highlight of the week was being guest speaker at an RMIT University forum on Tuesday evening - the topic being the technological singularity as postulated by Ray Kurzweil (drawing on the work of Vernor Vinge, Damien Broderick, and others). This turned into a surprisingly wide-ranging and enjoyable philosophical discussion, with excursions into utilitarian theory, philosophy of mind, philosophy of personal identity, and just about every other area of contemporary thought that could shed light on the issue. Thanks to John Lenarcik for inviting me.

Now to catch up on some reading and thinking for the next few days, I hope.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Money for anti-ageing research

The news around the traps this morning is that Peter A. Thiel, co-founder and former chief executive officer of PayPal, has made an announcement pledging US$3.5 million to help support the Methuselah Foundation's anti-ageing research. The Methuselah Foundation is the organisation set up by Aubrey de Grey to research technological means to halt or postpone ageing. De Grey argues that the ageing process can be broken down into seven more specific processes in our bodies, all of which are, in principle, capable of being retarded or even reversed. If we could control them, then very long or even indefinite lifespans are possible.

Three cheers for Aubrey!

Now, I'm not at all qualified to comment on the soundness of de Grey's theoretical work, but if private money is being put up to test it, then that's a great step forward from my particular viewpoint. I'd welcome some public money going into the enterprise as well, though for now there's an argument for prioritising it to more mainstream anti-ageing research, such as that of S. Jay Olshansky and his colleagues.

It totally baffles me why anyone wants to argue that ageing is something we should welcome as individuals - though it's true that there would be cumulative social impacts that we can't predict, if everyone could in fact live forever. If we could predict them all, we might not consider all the outcomes desirable. That is enough for me to doubt the claim that a quest for a "cure" for ageing is morally obligatory in any simple sense. The question is, "Morally obligatory against what background?" The social changes would be so drastic that I don't think our ordinary moral thinking even applies in any straightforward way - it's like trying to apply Newtonian physics, or pre-Newtonian physics, to calculate the properties of objects moving at relativistic velocities. (Actually, that's a problem for many attempts to apply our inherited moral norms to choices that confront us in the twenty-first century. This often frustrates me when I read the work of other moral philosophers. They seem to think that our moral norms are our masters; I think of them as our tools. We need to design new tools for new circumstances.)

In the end, some of this comes down to personal values, and the overriding one from my viewpoint is that of retaining and exercising our capacities for as long as possible, rather than suffering the humiliations of decline and dependence. Despite all the pro-death propaganda around, I'm betting that this value will eventually prevail. It's in our nature to be dissatisfied with at least some of our limitations, and we will continue to search for technological means of pushing them back. We may not always want more (possession of a radar sense is surely beyond the horizon of desire for most people), but we certainly want to hold on to what we have, and to rebel against the erosions of time.

When and if we are able to extend the normal period of adult health, vitality and robustness, there will have to be consequential changes in our social arrangements and our inherited moral norms, but that's not something I'm afraid of. Kindness and love, curiosity and joy will still exist in a society of very long-lived people. If a whole lot of other things have to change, then let it happen.

Three cheers for Aubrey!

Now, I'm not at all qualified to comment on the soundness of de Grey's theoretical work, but if private money is being put up to test it, then that's a great step forward from my particular viewpoint. I'd welcome some public money going into the enterprise as well, though for now there's an argument for prioritising it to more mainstream anti-ageing research, such as that of S. Jay Olshansky and his colleagues.

It totally baffles me why anyone wants to argue that ageing is something we should welcome as individuals - though it's true that there would be cumulative social impacts that we can't predict, if everyone could in fact live forever. If we could predict them all, we might not consider all the outcomes desirable. That is enough for me to doubt the claim that a quest for a "cure" for ageing is morally obligatory in any simple sense. The question is, "Morally obligatory against what background?" The social changes would be so drastic that I don't think our ordinary moral thinking even applies in any straightforward way - it's like trying to apply Newtonian physics, or pre-Newtonian physics, to calculate the properties of objects moving at relativistic velocities. (Actually, that's a problem for many attempts to apply our inherited moral norms to choices that confront us in the twenty-first century. This often frustrates me when I read the work of other moral philosophers. They seem to think that our moral norms are our masters; I think of them as our tools. We need to design new tools for new circumstances.)

In the end, some of this comes down to personal values, and the overriding one from my viewpoint is that of retaining and exercising our capacities for as long as possible, rather than suffering the humiliations of decline and dependence. Despite all the pro-death propaganda around, I'm betting that this value will eventually prevail. It's in our nature to be dissatisfied with at least some of our limitations, and we will continue to search for technological means of pushing them back. We may not always want more (possession of a radar sense is surely beyond the horizon of desire for most people), but we certainly want to hold on to what we have, and to rebel against the erosions of time.

When and if we are able to extend the normal period of adult health, vitality and robustness, there will have to be consequential changes in our social arrangements and our inherited moral norms, but that's not something I'm afraid of. Kindness and love, curiosity and joy will still exist in a society of very long-lived people. If a whole lot of other things have to change, then let it happen.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Hall of ... um ... fame

Just received confirmation that I am now included in Marquis Who's Who in the World, though I have no idea how it happened - it wasn't a self-nomination, I just filled out the form when they contacted me. Thank you to whoever gave them my name.

I'd be asking for congratulations, but let's face it: getting into the Marquis Who's Who volumes, like this one and Who's Who in America may not be as difficult as it sounds. Then again, all the who's who type books, including the original Who's Who, which covers eminent Britons, seem to have odd criteria. I suppose I might as well enjoy it, but I'm not going to be buying a copy of my own for a zillion dollars.

I'd be asking for congratulations, but let's face it: getting into the Marquis Who's Who volumes, like this one and Who's Who in America may not be as difficult as it sounds. Then again, all the who's who type books, including the original Who's Who, which covers eminent Britons, seem to have odd criteria. I suppose I might as well enjoy it, but I'm not going to be buying a copy of my own for a zillion dollars.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Even harder than it looks

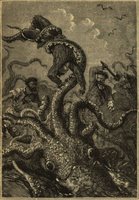

Further to my previous post, I'm having one of those kinds of days - i.e., of the kind represented by this image. It seems illogical to go very deeply into the history of science fiction without first offering some sort of account of what it actually is. But of course, it is notoriously difficult to define, and all definitions are controversial. Just why is very difficult to explain to someone who lacks a fairly detailed knowledge of the history of the field. This seems like a catch-22 situation. In the more leisurely space of a book, it would be possible to deal with it by writing chapters that tackle the problems from different angles. That's not possible in a relatively short article.

Further to my previous post, I'm having one of those kinds of days - i.e., of the kind represented by this image. It seems illogical to go very deeply into the history of science fiction without first offering some sort of account of what it actually is. But of course, it is notoriously difficult to define, and all definitions are controversial. Just why is very difficult to explain to someone who lacks a fairly detailed knowledge of the history of the field. This seems like a catch-22 situation. In the more leisurely space of a book, it would be possible to deal with it by writing chapters that tackle the problems from different angles. That's not possible in a relatively short article.I suspect the solution will eventually involve writing something much simpler than I'd really like.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Science fiction in 3500 words

Yes, that's my current task - produce the definitive 3,500 word article on science fiction for The Literary Encyclopedia (an on-line reference work). This is going to have to be a very carefully chosen 3,500 words - as I wrestle with it, I become even more aware of the magnitude of the field and the issues that I'm trying to sum up here.

Back to the grindstone. ...

Back to the grindstone. ...

Saturday, September 02, 2006

Short course on transhumanism

I've signed up with my School (at least I think it's all signed up now) to teach a short introductory course on transhumanism in October - aimed at honours-level philosophy students (and/or auditing by postgrads). The descriptive material that I prepared reads as follows:

"The transhumanist agenda - ambitions and critiques."

Convenor: Russell Blackford

Transhumanism is an intellectual and cultural movement that advocates the use of technology for such purposes as enhancement of human physical and cognitive capacities, alteration of moods or psychological predispositions, and radical extension of the human life span (possibly including a "cure" for the ageing process). Typically, the aim is to negotiate a transition from human-level capacities to capacities so much greater as to merit the label "posthuman" for those who possess them. Some transhumanist thinkers also advocate various other technologies that do not exactly meet this description, e.g. artificial intelligence of a very strong kind, molecular-level engineering and manufacturing, and technological methods for "uplifting" the cognitive capacities of non-human mammals to something approximating the human level. Finally, transhumanists analyse the possible risks, as well as potential benefits, of emerging or anticipated technologies, and formulate proposals that are intended to lessen risks without losing the claimed benefits.

An agenda such as this raises many questions for philosophical consideration. Some questions relate to the transhumanist agenda's practicality and coherence. For example, can a coherent definition be given of "enhanced", as opposed to merely "altered", capacities? If we were transformed into beings with vastly enhanced (or radically altered) capacities, would this be compatible with the preservation of our existing identities and/or with our survival of the transformation? Other questions relate more to how we should react, individually and collectively, to transhumanist proposals. For example, are the transformations advocated by transhumanists desirable for us as individual people? Are they socially manageable? Are they morally compulsory, permissible, or forbidden - assuming there is some real prospect that they can be achieved? Can we be discriminating in accepting some parts of the transhumanist agenda, while rejecting others? On what grounds? What methodologies can be employed to assess such "big picture", and possibly high risk, proposals? Can resistance to them sometimes be explained by invoking irrational features of human psychology?

All these questions and others straddle issues of interest to, at least, metaphysics, ethics, and political philosophy.

The readings below are all available online. A small number of additional readings will be selected and made available prior to commencement of the course. For students wishing to write on topics raised in this course, more detailed readings can be provided by the convenor. Those students are also advised to consult James Hughes, Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future (Westview Press, 2004) (on reserve in the Matheson Library), which offers one comprehensive version of the transhumanist agenda.

Readings

Bailey, Ronald. 2004. "Transhumanism: the most dangerous idea?".

Bostrom, Nick. 2002. "Existential risks: analyzing human extinction scenarios".

Bostrom, Nick. 2005. "A history of transhumanist thought".

Fukuyama, Francis. 2004. "The world's most dangerous ideas: transhumanism".

I'll be fascinated to see what interest this attracts. Meanwhile, I need to choose some further readings for the participants and to work out how best to conduct the course over three time-slots of an hour or two each.

Clearly, there's a great deal raised by transhumanist thought that young analytic philosophers could sink their methodological teeth into - whether they find the overall idea of "going posthuman" attractive or repellent (or just intriguing). The obvious issues range from the coherence of human beings wishing to be posthuman to the problems of distributive justice if the technology enabling them to do so becomes available in an unequal world. We'll see what happens. Ideally, it might encourage someone to do an interesting research paper.

"The transhumanist agenda - ambitions and critiques."

Convenor: Russell Blackford

Transhumanism is an intellectual and cultural movement that advocates the use of technology for such purposes as enhancement of human physical and cognitive capacities, alteration of moods or psychological predispositions, and radical extension of the human life span (possibly including a "cure" for the ageing process). Typically, the aim is to negotiate a transition from human-level capacities to capacities so much greater as to merit the label "posthuman" for those who possess them. Some transhumanist thinkers also advocate various other technologies that do not exactly meet this description, e.g. artificial intelligence of a very strong kind, molecular-level engineering and manufacturing, and technological methods for "uplifting" the cognitive capacities of non-human mammals to something approximating the human level. Finally, transhumanists analyse the possible risks, as well as potential benefits, of emerging or anticipated technologies, and formulate proposals that are intended to lessen risks without losing the claimed benefits.

An agenda such as this raises many questions for philosophical consideration. Some questions relate to the transhumanist agenda's practicality and coherence. For example, can a coherent definition be given of "enhanced", as opposed to merely "altered", capacities? If we were transformed into beings with vastly enhanced (or radically altered) capacities, would this be compatible with the preservation of our existing identities and/or with our survival of the transformation? Other questions relate more to how we should react, individually and collectively, to transhumanist proposals. For example, are the transformations advocated by transhumanists desirable for us as individual people? Are they socially manageable? Are they morally compulsory, permissible, or forbidden - assuming there is some real prospect that they can be achieved? Can we be discriminating in accepting some parts of the transhumanist agenda, while rejecting others? On what grounds? What methodologies can be employed to assess such "big picture", and possibly high risk, proposals? Can resistance to them sometimes be explained by invoking irrational features of human psychology?

All these questions and others straddle issues of interest to, at least, metaphysics, ethics, and political philosophy.

The readings below are all available online. A small number of additional readings will be selected and made available prior to commencement of the course. For students wishing to write on topics raised in this course, more detailed readings can be provided by the convenor. Those students are also advised to consult James Hughes, Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future (Westview Press, 2004) (on reserve in the Matheson Library), which offers one comprehensive version of the transhumanist agenda.

Readings

Bailey, Ronald. 2004. "Transhumanism: the most dangerous idea?".

Bostrom, Nick. 2002. "Existential risks: analyzing human extinction scenarios".

Bostrom, Nick. 2005. "A history of transhumanist thought".

Fukuyama, Francis. 2004. "The world's most dangerous ideas: transhumanism".

I'll be fascinated to see what interest this attracts. Meanwhile, I need to choose some further readings for the participants and to work out how best to conduct the course over three time-slots of an hour or two each.

Clearly, there's a great deal raised by transhumanist thought that young analytic philosophers could sink their methodological teeth into - whether they find the overall idea of "going posthuman" attractive or repellent (or just intriguing). The obvious issues range from the coherence of human beings wishing to be posthuman to the problems of distributive justice if the technology enabling them to do so becomes available in an unequal world. We'll see what happens. Ideally, it might encourage someone to do an interesting research paper.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)